Four Types of Songs of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn"

Children’s songs – dance songs – satirical songs. Among Mahler’s early songs for voice and piano is a number of nursery songs, including variants in the form of dance songs and satirical songs. Some of them were actually written for children – those of Marion von Weber in Leipzig. But even in these songs, we soon notice a new tone, a tone in which mischievousness alternates with vicious satire, lending these songs a hidden depth and ensuring that they are by no means as naïve or straightforward as they otherwise seem. The folk-like design of many of them is merely the basis on which Mahler expends his playful humour with positively virtuosic skill.

Scenes from nature – tales and parables. During the Age of Romanticism the contemplative, sentient individual projected his or her own emotions on to nature, which became an object of yearning, allowing people to escape from the confines of their humdrum lives and in the guise of the “blue flower” becoming a symbol of an entire philosophical outlook. Mahler, by contrast, saw in nature an “instrument on which the universe plays”, while using the images and symbols of folk songs and Romanticism to show us how in nature we are delivered up to a force over which we have no control, a force that can be both omnipresent and impersonal and unfeeling. “No one, of course, realizes that this nature contains within it all that is frightening, great and lovely. It always strikes me as odd that most people, when they speak of ‘nature’, think only of flowers, little birds, woodland smells and so on. No one knows the god Dionysus, or the great Pan.”

This world and the next. “For this I need the voice and simple expression of a child, just as – from the sound of the little bell onwards – I imagine the soul in Heaven, where, in its pupal state, it has to start all over again as a child.” This is how Mahler described the fourth movement of his Second Symphony, “Urlicht”, and it is a remark that contains within it the essence of his thoughts on death and resurrection, the doctrine of rebirth and transformation and the sort of naïve faith that we associate with children, all of which finds expression in his Wunderhorn songs. For a time he planned to head one of his symphonic movements “What the child tells me”. The reference to a “pupal state” also recalls the second part of Goethe’s Faust, adding an extra, philosophical dimension to everything we associate with children. But we must never lose sight of the fact that in songs that are placed in the mouths of children there is a playful element that reflects a carefree, innocent humour.

The fates of soldiers and other individuals. Within the comparatively limited range of texts that Mahler chose for his songs, pride of place goes to those that are set in the world of soldiers: qualitatively and quantitatively, this is the largest group. Writers seeking to explain this preponderance have often ascribed it to Mahler’s background and, more especially, to the barracks that were located in Iglau (now Jihlava), the imperial regional centre in Moravia where the composer spent his childhood and adolescence.

But soldiers’ songs were almost always affirmative in tone until well into the 20th century, even glorifying the lives of their subjects – and this applies equally to the functional songs sung by the military and to the folk songs and art songs that take the military as their starting point. Mahler, conversely, adopts a completely different approach to the subject: his heroes are either rebellious free spirits or, more often, losers, victims, deserters and men who have been condemned to death or who have already fallen in battle. Today’s Mahlerians may regard this as self-evident, and if Mahler himself had lived longer, it is unlikely that anyone who is familiar with his symphonies would number him among the many intellectuals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire who greeted the events of 1914 as a form of liberation. But it is always worth re-emphasizing the extent to which his choice of texts set him apart from his contemporaries.

Even so, it remains an open question why Mahler took such a sustained interest in the themes of suffering, separation, death and execution during times of war. After all, he was never obliged to serve in the army, nor was he or any of his family ever directly involved in war and its consequences. The momentous Battle of Königgrätz (now Sadova) in 1866 must have left its mark on the garrison town of Iglau, but Mahler never mentioned it as a formative childhood experience. Rather, it is difficult to avoid the impression that as both man and artist Mahler felt a visionary presentiment of the new century, with all its terrible developments and conflicts. (It needs to be stressed, however, that only later did man’s inhumanity to man assume a dimension that no one at the time could have anticipated.) Mahler must also have been convinced that the individual fates of all the innocent people who become victims in the cogs of our political rulers can find viable expression in the most “private” of all musical forms, the song.

© Renate Stark-Voit and Thomas Hampson, 2010

Translation: Stewart Spencer

File Download

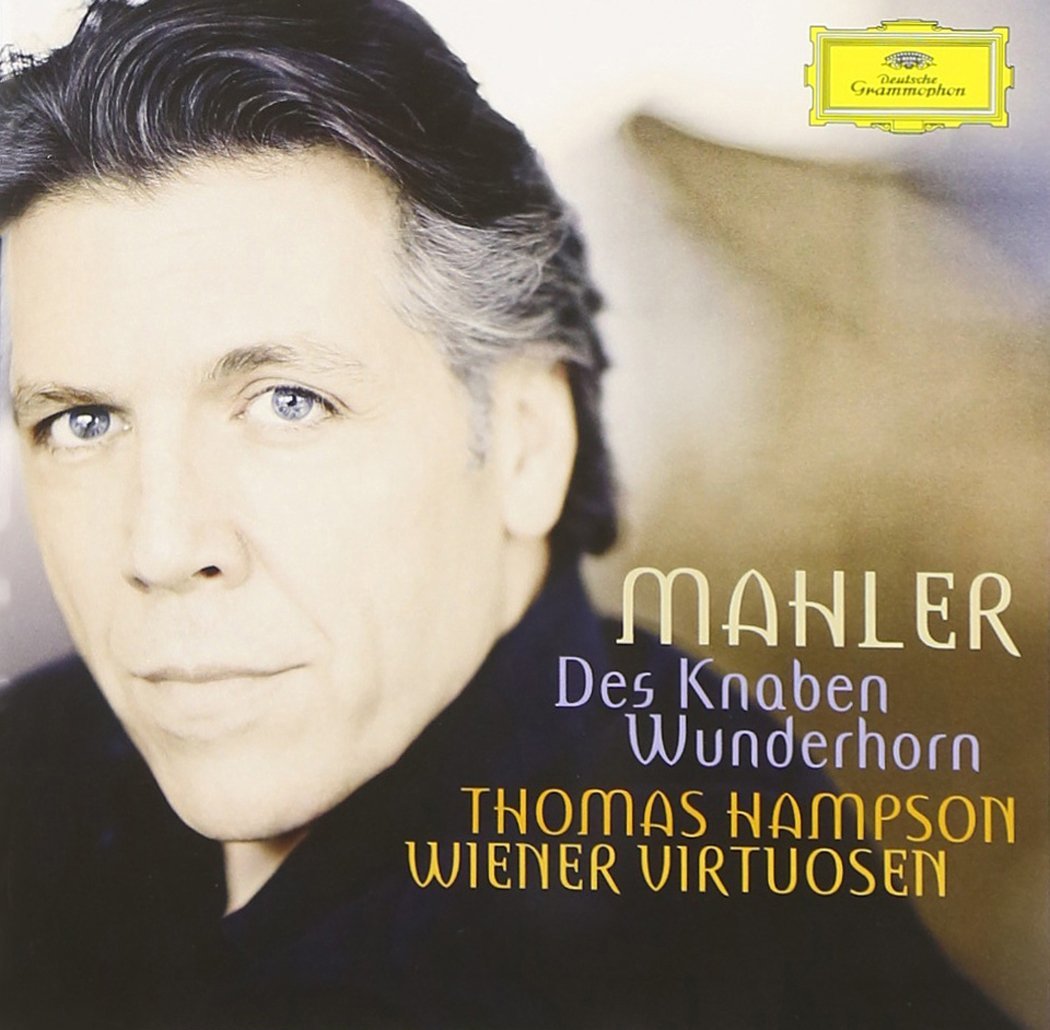

Essay from the CD booklet of the 2011 Deutsche Grammophon recording of Gustav Mahler’s "Des Knaben Wunderhorn" with Thomas Hampson and the Wiener Virtuosen. Copyright 2011 / This project was funded by the Hampsong Foundation.

Four-types-of-songs-of-Des-Knaben-Wunderhorn (pdf / 88.76 KB)Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Thomas Hampson, baritone

Wiener Virtuosen

Deutsche Grammophon, 2011