Elinor Remick Warren: An American Romantic

In her book Unsung: A History of Women in American Music, Christine Ammer notes that Elinor Remick Warren stands as “the only woman among the group of prominent American neo-Romanticists that include Howard Hanson, Samuel Barber, and Gian Carlo Menotti.” Warren never chose to set herself apart from the musical mainstream as a “woman” composer and frequently repeated her belief that “there is no gender in music.” However, in the early years of her career she stood, along with Amy Beach, as one of the few significant American women composers in a field almost entirely dominated by men.

Warren entered the world with the new century, on February 23, 1900. Her mother was a fine amateur pianist who had studied with a pupil of Liszt. Her father, a Los Angeles businessman, had once considered a concert career as a tenor. By the time Elinor arrived, he had confined his singing to evenings at home, accompanied by his wife, and to his church choir, as well as several of the excellent choral groups that flourished in Los Angeles during the first half of the century.

From the beginning, the Warrens’ only child was exposed to music. Besides music in the home, she was taken by her parents to hear recitals by great artists of the day who passed through Southern California on their concert tours; she also attended matinee performances of the Los Angeles Symphony, forerunner of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Her early affinity for choral music was stimulated by accompanying her father to rehearsals and performances of the Orpheus Club, a Los Angeles men’s chorus of which he was president.

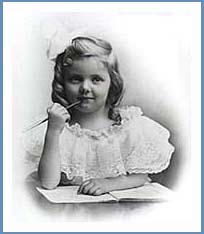

At the age of four, Elinor liked to sit beside her mother at the piano and pick out pieces which the astonished parent copied into a notebook. Not until she was five did the youngster begin music lessons. She recalled that shortly thereafter she was able to do the copying herself.

Luck was with Elinor when her parents chose Kathryn Montreville Cocke to be her first music teacher. Miss Cocke had received her training at the New England Conservatory of Music and used a method devised by Evelyn Fletcher Copp, a highly successful pedagogue who applied the principles of kindergarten teaching to music.

In 1912, Elinor’s family took her to England and the Continent for seven months. The impressionable child never forgot the experiences of that trip. Her diary is replete with superlatives about the musical performances to which she was treated. Prior to leaving, she had studied the Wagner “ring” cycle with her mother, and the performances of Wagner operas she heard in Munich and Paris received ecstatic attention in her trip diary. “‘Siegfried,’ which we saw last evening,” she wrote, was perfectly glorious and I enjoyed it much more than I can say. The last scene of the last act — was — !!!! when Brunnhilde sang so gloriously.”

Kathryn Cocke and a group of younger pianists, fresh from European study who assisted her, remained Elinor’s music teachers until her graduation from high school. By this time, she had developed into a skillful pianist and had continued composing, primarily for solo voice and chorus.

During her sophomore year in high school Elinor began the study of theory and harmony with a well-known local composer, Gertrude Ross. Ross urged her to send some of the music she was writing to New York publishers. Elinor chose one of her vocal solos, A Song of June, which she sent to G. Schirmer. She was surprised when the company sent her a contract.

After graduation from Westlake School, Elinor spent one year at home, studying with Ross and taking piano master classes with Harold Bauer and Leopold Godowsky. In 1919, she entered Mills College as a music major. However, after completing the freshman year, so anxious was she to get on with her career that she prevailed upon extremely reluctant parents to let her go East for further study. At the age of 20, she arrived in New York, where she spent the next five years working with the musicians she had already chosen to be her mentors: well-known art song composer and accompanist, Frank LaForge and composer/organist Dr. Clarence Dickinson, head of the music department at Union Theological Seminary.

Through LaForge, the young composer was introduced to many of the important singers of the day. At the age of 21, she accompanied the great Metropolitan Opera contralto Margaret Matzenauer at New York’s Carnegie Hall as she sang one of the young composer’s early songs, Heart of a Rose. Soon Warren was in demand by singers both as composer and accompanist. In her early 20s, she toured with Matzenauer and with stars such as Florence Easton, Richard Crooks, and Lawrence Tibbett, the latter a childhood friend from Los Angeles.

Warren had brought with her to New York a sheaf of songs and choruses which promptly found favor with New York publishers. In one year — 1922 — eleven of her songs and choral pieces were published by various major music firms. These publications prompted composer Deems Taylor, writing in a New York newspaper, to comment, “The composer, Elinor Remick Warren, has ideas, and an undeniable gift for song writing.”

Along with composing, Warren also found herself in demand as a piano soloist. In 1923 and again in 1925, she made a successful series of recordings for a New York record firm of piano solos from her tours as assisting artist with singers. In 1923 and 1926, she appeared as piano soloist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. This phase of her career continued until the 1940s, when she gave up touring to concentrate solely on her career as a composer.

Beginning in 1932, Warren moved into the larger orchestral forms withThe Harp Weaver, a work for women’s chorus, orchestra, and baritone soloist, which sets a poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay, who had won the Pulitzer Prize in 1922. The work’s New York premiere in 1936 brought Warren critical praise, and dual interests in orchestral and vocal music dominated her output from then on. Warren was one of the few Americans to compose extensively in the choral-orchestral medium. Her catalogue contains more than 90 works for chorus, including a significant number with orchestra.

The Legend of King Arthur was only the second of Warren’s major compositions scored for orchestra. The idea for this work came to the composer while still at Westlake School, when her English teacher read Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King to Elinor’s class. Later she recalled, “I was so thrilled with that part of it called ‘The Passing of Arthur.’ It just took hold of me, and, though it was beyond me then, I knew that one day I would set it to music.”

Warren embarked upon the choral symphony in the mid-1930s, later remembering the inspiration she experienced throughout its writing; how she could hardly wait each morning to begin work; the excitement she felt about every aspect of its creation.

Originally the composer titled her composition The Passing of King Arthur closely following the Tennyson title. However, after several major performances and before publication of a newly revised edition in 1974, she changed the work’s title, substitution Legend for Passing. She gave as her reason the fact that the work as she had envisaged it combines a very descriptive and atmospheric first half with a more spiritual second half, the entire work not being solely occupied with the king’s “passing.”

King Arthur had its world premiere in 1940, conducted by the celebrated Albert Coates, who had come from England for a series of appearances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Warren recalled the care with which Coates prepared her composition, even bringing various sections of the orchestra to her house for rehearsals in he presence. The premiere performance was broadcast to a nationwide radio audience and established Warren’s reputation as an important composer. A year later, Sir John Barbirolli conducted the work’s Intermezzo in a concert at the Hollywood Bowl.

Warren’s neo-Romantic leanings as a composer express themselves in her love of natural beauty – particularly scenes from the American West, which are her inspiration for a number of compositions, most notably her orchestral works The Crystal Lake, Along the Western Shore, Suite for Orchestra, and her song cycle with orchestra, Singing Earth.

Mysticism is another prominent theme in many of Warren’s major choral works such as King Arthur, The Harp Weaver, Abram in Egypt, andRequiem, which was commissioned by choral conductor Roger Wagner. A champion of Warren’s choral music, Wagner premiered most of the composer’s major choral-orchestral compositions and presented two performances of The Legend of King Arthur with the Los Angeles Master Chorale.

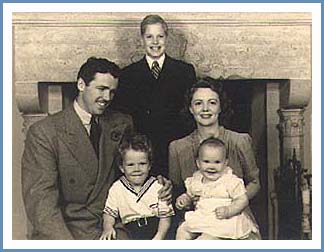

Throughout her career, Warren made highly individualistic choices which tended to remove her from the musical mainstream in America, but which allowed her to remain creatively independent. Aware that most composers left the Western United States to live and work in New York, the center of American musical life, Warren chose instead to spend her creative life in Los Angeles, where she had earlier found her inspiration. When she married happily and had three children, she combined her life as wife and mother with her work as a composer – vowing that each nurtured the other. When many composers were moving towards more “modern” idioms, Warren remained true to the neo-Romantic vision which remarkably mirrored her own personality. Advised that a composer would be wise to work in the smaller forms in order to get more performances, Warren ignored the advice, continuing to compose on the grand orchestral scale that she loved. Her music, accessible to audiences and characterized by well-crafted, emotionally intense and colorful compositions, had few detractors during her lifetime.

An early marriage in 1925 ended in divorce. Warren’s second marriage in 1936 to film producer and businessman Z. Wayne Griffin lasted until Griffin’s death in 1981. They had two sons and a daughter.

The composer continued to work until shortly before her death, from cancer, at age 91. Her career remains one of the longest and most prolific in American musical history.

© The Elinor Remick Warren Society, used here with permission

File Download

Download this biography as a PDF

Elinor Remick Warren: An American Romantic (pdf / 51.12 KB)