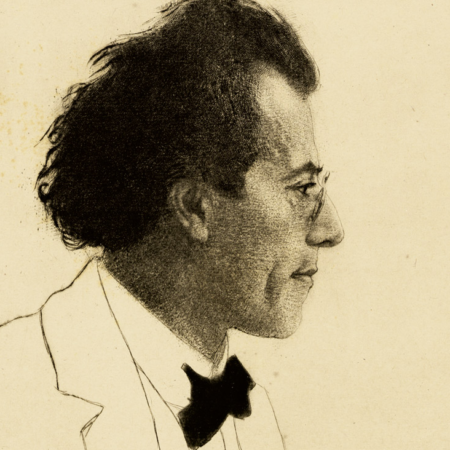

Mahler’s “Urlicht” and the Second Symphony

A conversation between Thomas Hampson and Renate Stark-Voit.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 1 of 10)

In this segment of an interview between baritone Thomas Hampson and scholar Renate Stark-Voit, Hampson introduces Stark-Voit as well as some of their topics of discussion, including Bildersprache, Gustav Mahler, and “Des Knaben Wunderhorn.’ Stark-Voit gives some background on Achim von Armin and Clemens Brentano, the writers of the original text collection “Des Knaben Wunderhorn,” published between 1805 and 1808. Hampson and Stark-Voit discuss the influence of German nationalism in assembling the stories of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn,” and Stark-Voit also brings up Goethe and his involvement in “Des Knaben Wunderhorn.”

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 2 of 10)

Thomas Hampson explains the driving forces behind assembling the text collection “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” and the need to articulate the “Volk” in literature in early 19th century Germany. Hampson and Renata Stark-Voit discuss their interest in the literature itself, apart from political and historical implications (as Hampson puts it, “the contemporary positioning of historical fact”). They also talk about the concept of “Ur” poetry both in a general context and in the context of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn.” The choices that Mahler made in choosing the texts of his song cycle and the philosophy of Johann Gottfried Herder are also discussed.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 3 of 10)

Thomas Hampson brings up the world of metaphor and its relationship to the “Bildersprache,” or “picture language,” in the texts of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn.” The topics of fragmentary (open-ended) literature and romantic irony are discussed in the context of 19th century German literature. Gustav Mahler’s relationship with literature, his literary choices and the importance of text in his music are also brought up. Hampson also discusses the profundity of third person narratives as compared to first person narratives and Mahler’s use of language as part of his compositional process.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 4 of 10)

Thomas Hampson and Renata Stark-Voit discuss the textual choices of composers, especially those of Mahler and how Mahler defended his choices of texts. Hampson brings up the original textual publication of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn,” published between 1805 and 1808, and the philosophy of and relationship between its compiler/writers, Achim von Armin and Clemens Brentano. Brentano’s religious fervor and Armin’s practicality are also discussed.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 5 of 10)

Thomas Hampson and Renata Stark-Voit discuss Mahler’s use of the poem “Urlicht” (from “Des Knaben Wunderhorn”) in his Second Symphony as well as the significance of “Bildersprache,” or “picture language,” in the context of that poem. They bring up Mahler’s compositional process, what “truth” was to him, and the place of the contemporary scholar and performer in relationship to Mahler. Hampson mentions Mahler’s call to conductors: “You have the responsibility to change my music.”

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 6 of 10)

In her conversation with Thomas Hampson, Renata Stark-Voit explains the genesis of the text of “Urlicht,” which is a “Todesgebet,” or prayer said at the bedside of a person who has just died. Hampson and Stark-Voit discuss the symbol of the rose and it’s color, and Hampson recites the text of the poem in English. Stark-Voit also explains the belief held by many philosophers and writers that the soul transforms into a child after a person’s death–the “Puppenstand.” She continues to clarify the details about “Urlicht” and brings up Mahler’s philosophy behind the piano reduction of the song.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 7 of 10)

In her discussion with Thomas Hampson, Renata Stark-Voit continues to clarify the details about “Urlicht” and brings up Mahler’s philosophy behind the piano reduction of the song, which was transcribed by Hermann Behn. Stark-Voit references her own experiences with Mahler’s manuscript and introduces a line from a Clemens Brentano poem written in the margin of Mahler’s “Urlicht.” The line reads: “Stern und Blume, Geist und Kleid, Lieb, Leit [und] Zeit, und Ewigkeit” (from Brentano’s “Es ist ein Schnitter, der heißt Tod”). Stark-Voit also mentions the significance of this poetic line in one of Brentano’s fairy tales, “Gockel, Hinkel, und Gackeleia.” Stark-Voit talks about the different manuscripts of this song in the archive at the Vienna Philharmonic and also about a curiosity: Mahler’s translation of the text of “Urlicht” into English. Stark-Voit gives more details about the “Bildersprache,” or “picture language,” present in this specific Brentano quote and whether or not this information is important in understanding the music.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 8 of 10)

Thomas Hampson and Renata Stark-Voit continue their discussion of Mahler’s Second Symphony and the poetry of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn.” In this part of the interview, Hampson and Stark-Voit talk about the “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” poem “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” and its role in the third movement of the symphony: the scherzo or “In ruhig fließender Bewegung.” They also discuss Mahler’s overall compositional process in the Second Symphony as well as the relationship between the song “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” from Mahler’s song cycle “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” and the symphonic movement based on that song.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 9 of 10)

Renata Stark-Voit expands on the idea of the “humoresque” in Gustav Mahler’s music and the musical language of the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony, including his direct reference to Robert Schumann’s song “Das ist ein Flöten und Geigen” (from “Dichterliebe”). Thomas Hampson brings up the influence of Czech music on this specific symphony movement, and both Hampson and Stark-Voit talk about the dramatic scene created by this music, as well as the mystery of Mahler’s overall compositional process, especially in how he assembled his Second Symphony.

Mahler’s “Urlicht” & The Second Symphony (Part 10 of 10)

Thomas Hampson and Renata Stark-Voit wrap up their conversation about Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony and specifically their discussion of the poem “Urlicht.” Hampson asks Stark-Voit about the angel figure in “Urlicht,” and, after discussing the voice type that Mahler asked for in regards to the singer of “Urlicht,” Hampson and Stark-Voit speculate on the image of the angel figure. They finish by discussing Mahler’s idea about the transcendence of life and his prophetic and philosophical nature. “We come to go. What’s in between is what matters.“