An Essay by Susan Youens

Courtesy of the Internationale Hugo-Wolf-Akademie

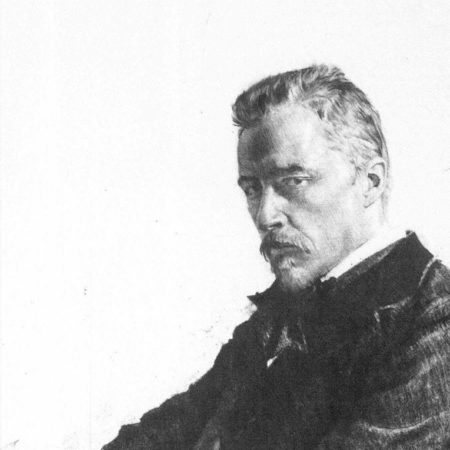

The Lieder of Hugo Wolf (1860-1903): Programm VI

In der Fremde – Ein Liederkreis – Sehnsuchtsvoll – Rollenlieder II

Essay by Susan Youens

In der Fremde – Ein Liederkreis

(In der Fremde – Ein Liederkreis song list)

Romanticism is inseparable from the theme of Wanderschaft—the literary highways and byways of Romantic Germany are strewn with wanderers, walkers, pilgrims, and poetic outcasts. It was inevitable that Wolf too would be drawn to this ubiquitous subject, with its underlying larger matters of identity, alienation, and outsider-status.

For a young song composer in the 1870s, the natural model was Schumann—Schumann’s poets, Schumann’s musical procedures. For the remarkable achievement that is Sie haben heut’ Abend Gesellschaft, Wolf chose a poem by one of Schumann’s favorite poets—the great and slippery Heinrich Heine—and, for the first (not the last) time in his works, creates a piano part in which sounds from the outside world are altered by the narrator’s perceptions. Uninvited by the poet, Wolf invents a salon-style waltz for the entertainment of the shadowy company inside the beloved’s house and then subjects the party-music pleasantries to the convolutions of a solipsistic mind, the result a dark precipitate of the previous graceful trivialities. At the end, Wolf takes the fury that is the by-product of futility and gives it free rein in the piano, after the poetic control exercised in words has stopped.

Over and over again, the bass line of the plangent Mir ward gesagt, du reisest in die Ferne—a lover’s lament over his beloved’s imminent departure—descends, falling away from the right-hand part, as if the singer beholds a repeated vision of increasing distance from the one he loves. Over and over, he tells her that his tears will be with her always, and we hear the tears flowing down his cheeks. The original Portuguese playwright and poet Gil Vicente, an early 16th-century master, bridges the transition between medieval literature and the new ways of Renaissance thought.

The early 16th-century Portuguese poet Gil Vicente, called the „Trobador,“ figures in the transition from medieval traits to Renaissance poetry; poems such as „Si dormis, doncell“ (Und schläfst du, mein Mädchen) were written in Castilian and—centuries later—paraphrased in German by Emanuel Geibel for the Spanisches Liederbuch (1852), an anthology immediately appropriated by composers such as Brahms, Schumann, Max Bruch, and many others. Wolf is, of course, famous for his unique, post-Wagnerian musical complexity, but every once in a while, he marries his signature tonal ingenuity to such lilting tunefulness that we are instantly captivated, and this is one of them. The rustic open fifths in the bass add to the folkloric atmosphere.

„Scarcely was my letter dispatched [to his friend Edmund Lang on 22 Feberuary 1888] than, taking the Mörike in hand, I wrote a second song, in 5-4 time and perhaps I may say that seldom has 5-4 time been so fittingly employed as in this composition. You too, a layman, will at once discover the 5/4 measure in the rhythm of the poem and understand the necessity for it,“ Wolf wrote his friend Edmund Lang on 22 February 1888 in the midst of his „miracle year“ of one glorious Mörike song after another. Mörike’s Jägerlied is fashioned in end-stopped trochaic pentameters, the last foot truncated and each line whole unto itself. Wolf’s emphasis on the first beat and the grace-noted fifth beat in the delightful introduction calls attention to the metrical anomaly prevailing throughout. In one of Wolf’s typical „dying away“ postlude, this sweet hunter-in-love recedes from view to the sound of hunting fanfares growing softer and softer.

Gildet paa Solhoug or Das Fest auf Solhaug (1855) was Henrik Ibsen’s first successful drama and one of his many portraits of unhappy marriage. Margit is married to Bengt, who she does not love and tries to poison; her kinsman Gudmund, who she does love, longs for Margit’s sister Signe. In her inset-Ballade, „Bergkönig ritt durch die Lande weit,“ Margit finds folkloric expression for her own dilemma: the mountain king frees Kirsten from Lord Hakon, then decks her with gold and carries her to imprisonment in the mountain as his bride. Wolf was asked to write incidental music for a Burgtheater production of the play and was initially enthusiastic—but not for long. This ballad cost him considerable pain before he could „sweat it out,“ but it is by far the most successful number in the score.

We do not know the source for Wolf’s Wanderlied (Aus einem alten Liederbuche), but its wanderer is an appealing addition to the long list of Romantic voyagers without a set goal; pointing out that no one asks the clouds and the winds where they are going, he launches himself happily on the wanderer’s way and announces that he won’t even ask himself „Wohin?“ This is a youthful song and more conservative in its harmonic language than the later works, but there are wonderful touches throughout: the crucial word „Wohin“ is twice emphasized by a sudden third-related shift, from G major to B major (very characteristic of Wolf), that is magical in its effect.

In Wandl’ ich in dem Morgentau, the Swiss realist writer Gottfried von Keller created another winning creature, a village maiden who wanders out into the meadows in the morning dew, catalogues Nature’s fruitfulness all around her and laments her own lack of love. Wolf paints a gentle, diatonic portrait of a winsome girl and of lilting, lovely Nature at the start and then infiltrates the music with more and more of his characteristic, far-reaching chromaticism. The descending chromatic lines at the end tell us how sad she is.

August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben was among the best Tendenz-Dichter of his day, a progressive who also wrote children’s songs and appealing portraits of daily life, including Des fahrenden Schülers Lieben und Leiden of 1824, an outstanding contribution to Vagantenlyrik down the ages. For his setting of Auf der Wanderung, Wolf creates the kind of vigorous Ländler-like song that would have delighted Haydn, that aficionado of Austrian folk music, and no wonder: the rhythms are irresistible.

On two different occasions in 1878 and 1879, Wolf turned to the often intensely melancholy poetry of Nikolaus Lenau, who made his own journey „in der Fremde“ to far-away New Harmony, Indiana (not far from where this note-writer currently lives) for a brief time and died in an insane asylum. The rising and falling chromatic bass line and tremolos in the introduction to Herbstentschluss already hint at a storm-tossed soul before a word is sung. It is loss in love that propels this wanderer out into a cold, hostile world, and one wonders if Wolf knew of Caroline Unger, the married Sophie von Löwenthal, or any of Lenau’s unhappy loves (Wolf himself would later fall in love with the married Melanie Köchert). In Nächtliche Wanderung, Wolf had already brewed up a gloomy, bell-haunted, tremolo-ridden tempest more than a year earlier, albeit with an angelic episode for guidance by the dead bride, its ethereal, treble, repeated chords clearly influenced by Liszt.

A lover setting out on a coach journey that takes him away from his beloved in Eichendorff’s In der Fremde I (one of a trilogy of songs with this same title) tells her in his thoughts that he is nonetheless always with her. For the forests, abysses, and valleys that go by his window, Wolf experiments with a Wagnerian combination of figures in the piano combining with the voice.

Homesickness as a literary theme is familiar from folklore and from 18th-century poetry about Swiss mercenaries abroad longing for their native land. Heimweh is Mörike’s variation on this theme, with its lad lamenting the distance from his beloved and the strangeness of everything around him. A Die schöne Müllerin-like brook bids him look at the forget-me-nots on its bank, but the lad cannot be consoled. Wolf sounds a mournful, slow, dactylic rhythmic pattern throughout.

After Wolf’s Heine Liederstrauß, he next transferred his allegiance to Eichendorff, setting „Erwartung,“ „Die Nacht,“ and Rückkehr. (The language in which Wolf describes Nature in his letters betrays the strong influence of Eichendorff). What Wolf called the typical „clair-obscur“ atmosphere of this poet’s nocturnal poems is on display in this return to a familiar place, only to venture out into the world again. We hear Wolf’s fondness for chain-of-thirds progressions as the poetic character roams the streets of a town he once knew (B-flat to D major to the opening F-sharp major), a tonal panorama to match the motion through darkened streets. This song, composed in 1883, is a lovely foreshadowing of the Eichendorff songs to follow in 1886, 1887, and 1888.

Restlessly shifting chords beneath a more diatonic vocal line celebrate Liebesfrühling, Hoffmann von Fallersleben’s variant on the ages-old equivalence between the arrival of spring and the arrival of love.

Sehnsuchtsvoll

Love—its joys, its sorrows—is a perennial theme in Lieder, and Wolf (who knew of both) wrote numerous songs about the many inflections of passion. Four of his early songs on aspects of love follow, including one („Nachruf“) composed during his first serious love affair with Valentine (Vally) Franck. She broke it off before his 21st birthday, and Wolf was, as we all are when first love ends, very upset for a time.

Friedrich von Matthisson’s 1792-3 poem Andenken („Ich denke dein“) was a veritable magnet for composers, including Beethoven, Schubert’s teacher Antonio Salieri, Schubert, Johann Zumsteeg, and Carl Maria von Weber. At age 17, Wolf already delights in far-flung harmonic and tonal gestures; we begin in a gently pastoral E major and pass through a „purple patch,“ ushered in by enharmony (Lisztian influence yet again) before returning to the home key and from there, going on more beautiful detours. The shift to the chord on the flatted sixth degree at the start of the final section is heart-stopping.l

By the 1870s, Heine’s famous poem Du bist wie eine Blume was a barbed-wire trap for the unwary, a text colonized by many composers, most famously by Schumann in his cycle Myrthen, Op. 25, no. 24. According to an anecdote in his friend Edmund Hellmer’s (the sculptor of Wolf’s exquisite tomb monument in Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof) Hugo Wolf, Erlebtes und Erlauschtes of 1921, Wolf may have used his close study of Schumann’s songs in order to learn good text declamation; he would later devise his own methods of declamatory vocal writing constituted differently from Schumann’s but in 1876-77, Schumann was this auodidact’s chosen model. Here, Wolf apes Schumann’s non-legato succession of chordal harmonies in the piano and duplicates the length and formal design of the earlier mini-masterpiece. But Wolf’s harmonies are in the treble register, above the male voice (an ethereal effect) at the beginning, and the dark underside of the mock-papal prayer comes out more strongly in Wolf than in Schumann.

Wolf fashions his setting of the Ständchen by the early 19th-century Prussian war hero-poet Theodor Körner (Schubert knew him personally) as an alternation between passages sung by a lover beneath his beloved’s window—perhaps the Viennese actress Antonie Adamberger to whom Körner was engaged—and piano passages in which we hear his wordless emotions. Fear of nocturnal spirits, echoing treble calls to her, rising passion followed by sinking quietude, all leading to the sweet declaration „Ich liebe,“ set to waves of harp-like chords.

Nachruf, like Eichendorff’s „Das Ständchen“ set to music by Wolf on 28 September 1888 (a masterpiece of song), contrasts past and present, serenades to the living and serenades to the dead, who might just, on hearing our song in memoriam, draw us up to join them in the heavens. The lengthy, strummed introduction, in which the piano imitates a lute, is colored by hints of darker harmonies, foreshadowing the music for the valleys descending into night and the dead who are no longer there. Hints of the recurring darkness tinge the final bell-like chords in the treble.

Rollenlieder II

When Wolf was on the hunt for poems by those earlier literary masters he revered that had not been set to music by his great predecessors, he was delighted to discover Eichendorff’s Rollenlieder, in which vivid personae of many kinds reveal themselves in song (this was also, Wolf realized, excellent preparation for composing the operas he yearned to write one day). These songs are often supremely challenging, both for the pianist and the singer: colorful characters receive emphatic music.

In Die Zigeunerin, a melodious gypsy girl roams the forest by night, takes a potshot at a stray cat at dawn, and fantasizes about a lover who must be a wanderer, and with Hungarian-style mustaches to boot. Wolf must have had a marvelous time inventing the spooky, Scotch-snap figures that make the forest a place to fear, the virtuosic leaps to portray the scared cat, and the gypsy girl’s humming and laughter. The forest nymph, or Waldmädchen, assumes three different forms in this song, also a virtuoso work-out: fire to burn the unwary, a deer who defies any huntsman to catch her, and a bird who finally sinks into the waves and perishes. And finally, the sailor of Seemanns Abschied bids a defiant farewell to the landlocked beloved and praises the seafaring life over that of soldiers and musketeers. Wolf, who delighted in musical onomatopoeia, brews up an angry tempest/reproach to the sweetheart and depicts sharks snapping in the waters and seagulls shrieking, the Flood come again, and a deliberate excess of octaves at the end. It is a thrilling conclusion.

The Author

In Cooperation with

The Lieder of Hugo Wolf (1860-1903): Programm VI

In der Fremde – Ein Liederkreis

(Susan Youens on In der Fremde – Ein Liederkreis)

Sie haben heut Abend Gesellschaft – text by Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), 18-25 May

1878

Mir ward gesagt, du reisest in die Ferne (Italienisches Liederbuch, Part I, 1892) – text trans. by Paul Heyse (1830-1914), 25 September 1890

Und schläfst du mein Mädchen (Spanisches Liederbuch, 1891) – text by Gil Vicente (c. 1465 – c. 1536), trans. by Emanuel Geibel (1815-1884), 17 November 1889

Ballade. Gesang Margits (from Drei Gesänge aus Ibsens ‚Das Fest auf Solhaug’, 1897) – text by Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906), 7 January 1891

Jägerlied (from Gedichte von Eduarde Mörike, 1889) – text by Eduard Mörike (1804-1875), 22 February 1888

Wanderlied (Aus einem alten Liederbuche) – text by Anonymous, 14-15 June 1877

Wandl’ ich in den Morgentau (from Alte Weisen, Sechs Gedichte von Keller, 1891) – text by Gottfried Keller (1819-1890), 8-23 June 1890

Auf der Wanderung – text by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben (1796-1874), 10 August 1878

Herbstentschluß – text by Nikolaus Franz Niembsch Edler von Strehlenau/Nikolaus Lenau (1802-1850), 8 July 1879

Nächtliche Wanderung – text by Nikolaus Lenau, 19-21 February 1878

In der Fremde l – text by Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (1788-1857). 27 June 1881

Heimweh (from Gedichte von Eduard Mörike) – text by Eduard Mörike, 1 April 1888

Rückkehr – text by Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, 12 January 1883

Liebesfrühling – text by August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben (1796-1874), 9 August 1878

Sehnsuchtsvoll

(Susan Youens on Sehnsuchtsvoll)

Andenken – text by Friedrich von Matthisson (1761-1831), 23-25 April 1877

Du bist wie eine Blume – text by Heinrich Heine, 18 December 1876

Ständchen – text by Theodor Körner, 25 March – 12 April, 1877

Nachruf – text by Joseph von Eichendorff, 7 June 1880

Rollenlieder II

(Susan Youens on Rollenlieder II)

Die Zigeunerin (from Gedichte von Eichendorff, 1889) – text by Joseph von Eichendorff, 19 March 1887

Waldmädchen (from Gedichte von Eichendorff) – text by Joseph von Eichendorff, 20 April 1887

Seemanns Abschied (from Gedichte von Eichendorff) – text by Joseph von Eichendorff, 21 September 1888