Part of Singers on Singing: Composer Profiles

This feature does not in any way set out to be comprehensive. Instead it offers the opportunity to hear audio files of comments by distinguished performers and scholars on elements of singing music by Claude Debussy. There are also relevant music clips, all of which are extracted from Warner Classics’ new 33 CD set “Claude Debussy – The Complete Works”, the first and only complete collection of recordings of Debussy’s music, comprising all his known works, including six pieces in world-premiere recordings made especially for their edition. An extract from one of these, the fragments of the opera La Chute de la maison Usher as they were in their sketches for singers with piano when Debussy set the work aside in 1916 (it was never orchestrated by him), is included in this feature “Singing Debussy”. We are deeply grateful to Warner Classics for generously allowing the use of all the extracts in this feature, as we are to them for granting the use of extracts from their famed catalogue elsewhere in our other Singing on Singers features.

Claude Debussy: The Complete Works

Available starting March 25, 2018

Warner Classics: 0190295736750

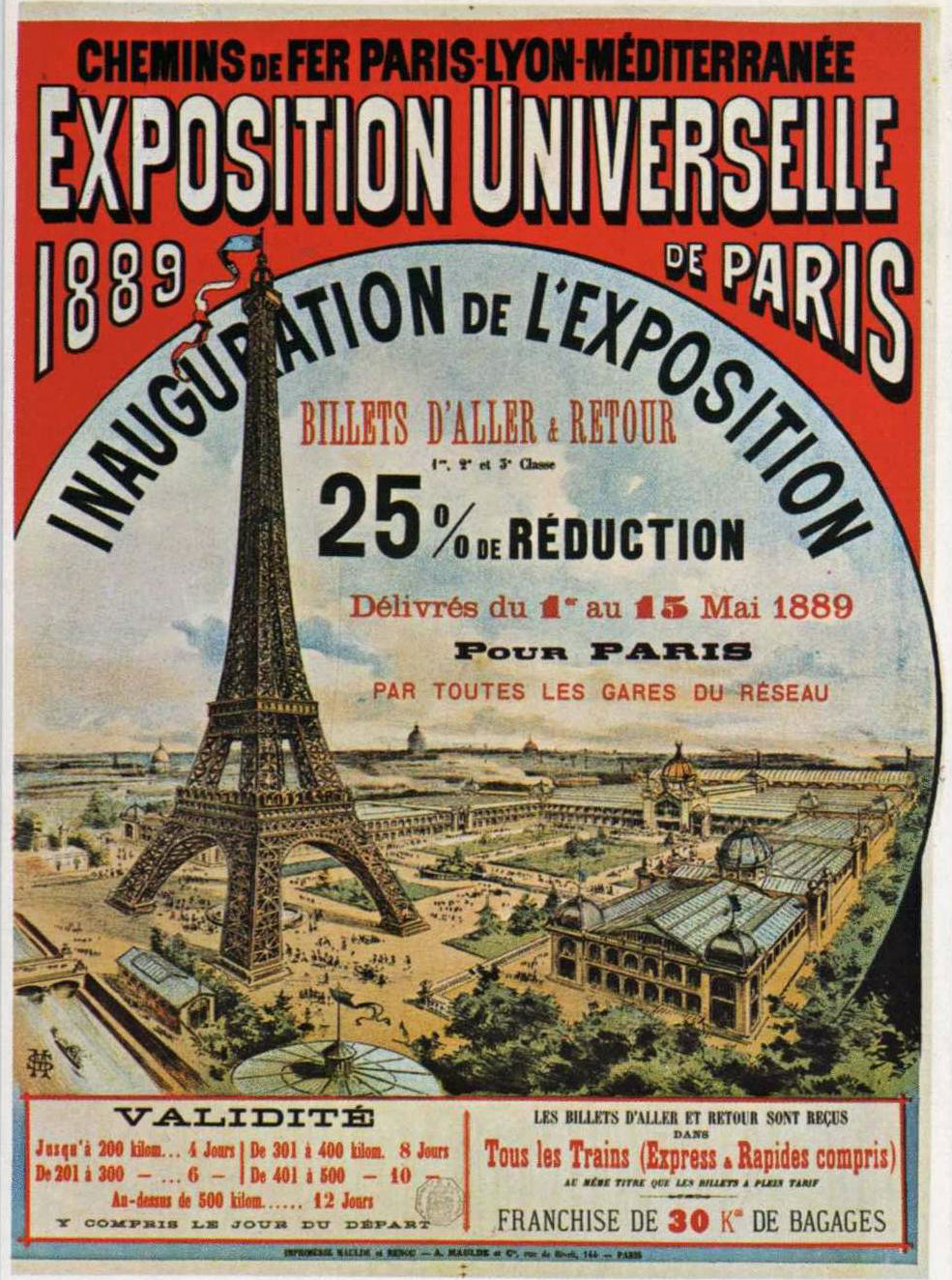

Debussy & the Exposition Universelle of 1889

Claude Debussy created a completely new kind of expressive magic and power in his music that revolutionised the musical world. Nature, people, and places: Debussy suggested them allusively and atmospherically in a new musical language that has to the present time felt forever fresh, free and spontaneous: almost as though it is being improvised on the spur of the moment.  It was after 1889, when he had been mesmerised by Eastern music, dance and theatre that had come to Paris in the Exposition Universelle, that the vital essence of his radical new style materialised, but even before this and especially in his early songs from 1879 onwards, he was composing a new kind of music in its harmonic freedom and iambic rhythmical spontaneity.

It was after 1889, when he had been mesmerised by Eastern music, dance and theatre that had come to Paris in the Exposition Universelle, that the vital essence of his radical new style materialised, but even before this and especially in his early songs from 1879 onwards, he was composing a new kind of music in its harmonic freedom and iambic rhythmical spontaneity.

The strong inspiration for these early songs was twofold: firstly, since his student years, Debussy had been profoundly interested in literature and especially French poetry, unusually so for a person at the Paris Conservatoire of Music at that time; and secondly, he had fallen in love with a lady for whom he prolifically wrote many songs in these early times. Blanche-Adélaïde Vasnier (sometimes known as Marie-Blanche Vasnier) was the wife of Parisian civil servant Eugène-Henri Vasnier, who offered support for the young Debussy, and he used to visit their home daily in the first few years of the 1880s. Madame Vasnier was an amateur soprano of considerable talent and Debussy was enchanted by her high coloratura voice – and more.

Denis Herlin, Director of the Institute of Musicological Research in the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and Chief Editor of the Durand Edition of Debussy’s Complete Works, takes up the story in the audio file, followed by an extract from Debussy’s setting of Paul Verlaine’s Pantomime.

LISTEN TO THE AUDIO CLIP BELOW

Track 1 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Denis Herlin discusses Debussy’s music inspired by Madame Vasnier, plus an extract from “Pantomime” (1883), sung by Natalie Dessay and accompanied by Philippe Cassard

“To Madame Vasnier. These songs which she alone has brought to life and which will lose their enchanting grace if they are never again to come from her singing fairy lips. The eternally grateful author”. Debussy wrote that inscription to Blanche-Adélaïde Vasnier in a dedication at the front of an album of song settings of poems by Paul Verlaine and Paul Bourget, composed especially for her. One of the Verlaine poems he set for her was Clair de lune, published in 1882 – but he was to create a vastly different sonic world around the same words when he set the poem again around 1890 and 1891.

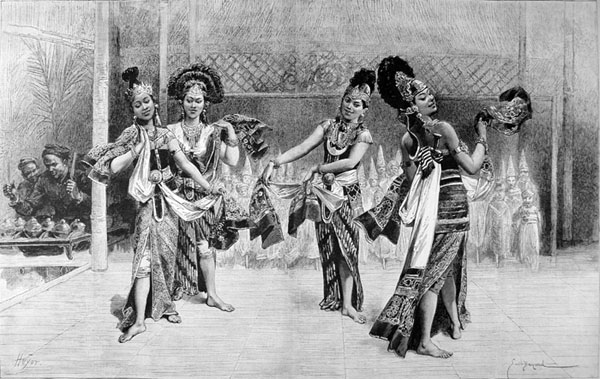

By then he had been astounded by an unexpected discovery that had changed his life.  In 1889, the year of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, a particularly ambitious World fair had been erected at the Champ de Mars in Paris. Debussy visited this Exposition Universelle, and he was captivated by one of the principal attractions: a Javanese gamelan ensemble performing with groups of exotic dancers in a construction of an Indonesian kampong village. He was entranced by the Eastern musical scales, and the feeling of freely developing impressions, and he later wrote: “Javanese rhapsodies, instead of confining themselves in a traditional form, develop according to the fantasy of countless arabesques”. The experience was a revelation for his new creativity. It opened his imagination to the conception of a new language and a new form, in which music could float, as it were, seemingly endlessly, as it was no longer locked into major and minor scales and/or chromatic tonality with orientations to harmonic resolutions (or conflicts of tension when there were no resolutions). Most importantly for Debussy he was conceiving this new style as a much closer musical correlation to the more intangible shapes, sonorities and impressions of symbolist poetry that inspired him so potently.

In 1889, the year of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution, a particularly ambitious World fair had been erected at the Champ de Mars in Paris. Debussy visited this Exposition Universelle, and he was captivated by one of the principal attractions: a Javanese gamelan ensemble performing with groups of exotic dancers in a construction of an Indonesian kampong village. He was entranced by the Eastern musical scales, and the feeling of freely developing impressions, and he later wrote: “Javanese rhapsodies, instead of confining themselves in a traditional form, develop according to the fantasy of countless arabesques”. The experience was a revelation for his new creativity. It opened his imagination to the conception of a new language and a new form, in which music could float, as it were, seemingly endlessly, as it was no longer locked into major and minor scales and/or chromatic tonality with orientations to harmonic resolutions (or conflicts of tension when there were no resolutions). Most importantly for Debussy he was conceiving this new style as a much closer musical correlation to the more intangible shapes, sonorities and impressions of symbolist poetry that inspired him so potently.

There is a strikingly effective example of the way his new style historically changed the course of composition and thus of performance when he set Verlaine’s Clair de Lune for the second time around 1890 and 1891. Denis Herlin explains this, followed by extracts from both mélodies – firstly the earlier version, followed by the later version.

LISTEN TO THE AUDIO CLIP BELOW

Track 2 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Denis Herlin discusses Debussy’s two settings of Verlaine’s “Claire de Lune” (the second setting is the third song in the composer’s first book of Fêtes Galantes), with extracts from the earlier version (1882), sung by Natalie Dessay accompanied by Philippe Cassard, and from the later version (1890/1891) sung by Veronique Gens accompanied by Roger Vignoles.

The more “distant” and mysterious impression in the second version, with looser and sometimes almost undefined tonality, might be said to reflect Debussy’s closer alignment with Verlaine’s symbolism in conjuring up an atmosphere through allusive sonic suggestion rather than graphic depiction. Crucially, it demands a wholly different singing style, one that is closer to poetic speech in many ways.

To Madame Vasnier.

Debussy's inscription to Blanche-Adélaïde Vasnier

These songs which she alone has brought to life and which will lose their enchanting grace if they are never again to come from her singing fairy lips.

The eternally grateful author

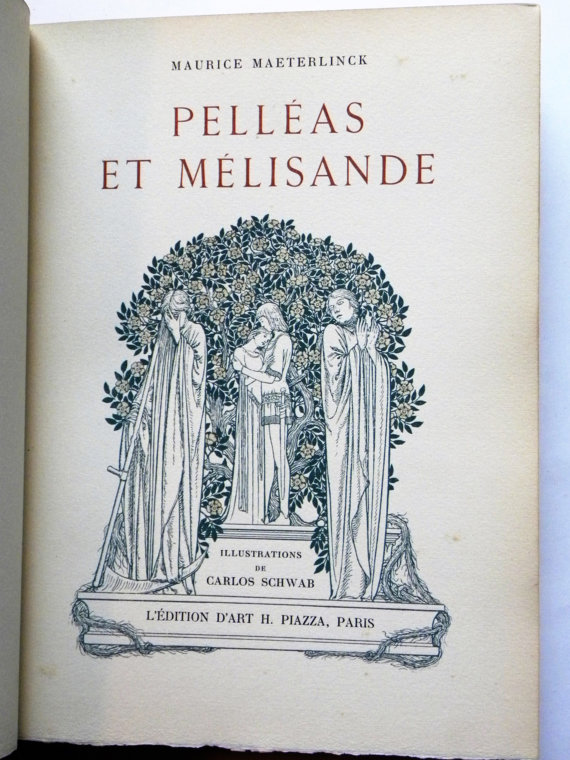

Debussy & Symbolism: Introducing Pelléas et Mélisande

However, symbolism for Debussy was not at all an academic principle – there was no such entity in his life! When in 1893 he went to see a new play receiving its then single performance at the Théâtre des Bouffes Parisiens, it was the emotive symbolism of the story and environmental ambience, conveyed however in personally natural, lifelike speech that so profoundly affected him. He realized that the synthesis of symbolism and actuality, paradoxical as that may seem, in the symbolist poet Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande was ideal for an opera of the same title: an opera that would be wholly unlike any written before. In a note “Pourquoi j’ai écrit Pelléas” (“Why I wrote Pelleas”) that he wrote in April 1902 in response to a request from the manager of the Opéra Comique prior to the premiere of his new opera there, Debussy said:

However, symbolism for Debussy was not at all an academic principle – there was no such entity in his life! When in 1893 he went to see a new play receiving its then single performance at the Théâtre des Bouffes Parisiens, it was the emotive symbolism of the story and environmental ambience, conveyed however in personally natural, lifelike speech that so profoundly affected him. He realized that the synthesis of symbolism and actuality, paradoxical as that may seem, in the symbolist poet Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande was ideal for an opera of the same title: an opera that would be wholly unlike any written before. In a note “Pourquoi j’ai écrit Pelléas” (“Why I wrote Pelleas”) that he wrote in April 1902 in response to a request from the manager of the Opéra Comique prior to the premiere of his new opera there, Debussy said:

“The drama of Pelléas which, despite its dream-like atmosphere, contains far more humanity than those so-called ‘real-life documents’, seemed to suit my intentions admirably. In it there is an evocative language whose sensibility can easily find an extension in the music and in the orchestral setting. I also tried to obey a law of beauty that seems notably ignored when it comes to dramatic music: the characters of this opera try to sing like real people, and not in an arbitrary language made up of worn-out clichés. That is why the reproach has been made concerning my so-called taste tor monotonous declamation, where nothing seems melodic. First of all it isn’t so. And furthermore, a character cannot always express himself melodically.”

The imagery, setting and atmosphere in Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande were entirely what Debussy had subconsciously been looking for when in 1889, not long after his experience of Javanese music and art at the Exposition Universelle, he had prophetically said to his former teacher Ernest Guiraud that, in response to Guiraud’s question as to what kind of poet he might have in mind for a possible opera libretto, he would need “one who only hints at what is to be said. The ideal would be two associated dreams. No place, nor time. No big scene. No compulsion on the musician, who must complete and give body to the work of the poet. Music in opera is far too predominant. Too much singing and the musical settings are too cumbersome. The blossoming of the voice into true singing should occur only when required. A painting executed in grey is my ideal…No discussion or arguments between the characters whom I see at the mercy of life or destiny.”

And it was the intimacy of situation, though within a scenario in which growing repressed jealousy festers into violence and murder, that most of all enthralled Debussy and inspired the novelty and greatness of his opera Pelléas et Mélisande – a work in which indeed “the characters…try to sing like real people” and in which indeed there is “No discussion or arguments between the characters…at the mercy of life or destiny”. Mélisande is willowy, alluring and mysteriously quiet. For reasons beyond her and most of the other characters’ understanding she exerts a strange power by saying and ostensibly doing very little. She is discovered by Prince Golaud, who finds her weeping by a well in a forest. Clearly she has been traumatically damaged by something, but neither Golaud nor anyone watching the opera ever find out what that might have been. Although she is at first unwilling, Golaud persuades her to come away with him, and the two get married. She is much younger than him, and when she meets his younger half-brother Pelléas who is at the time staying in the dank and dark castle where Golaud lives with his grandfather Arkel, his mother Geneviève, and his child son Yniold (from his deceased wife), Mélisande and Pelléas become attracted. They do not say that much to each other and no feelings of love are overtly expressed until one vital moment, even though Pelléas increasingly suggests his feelings, but gradually and inexorably suspicion and jealousy begin to ferment in Golaud’s mind as he senses the latent passions that are being aroused. Only at the end of the fourth of the five acts, at night in the park by the castle, does the denouement come when Pelléas, who has been ordered by Golaud to leave, finally says to Mélisande ‘je t’aime’ (‘I love you’) and to his astonishment she gently replies ‘je t’aime aussi’ (‘I love you too’). But now it is too late – Golaud has been secretly watching and he springs out on them from behind the bushes, killing Pelléas and later wounding Mélisande. In the next and final act she dies, not from her wounds but from giving birth prematurely to her and Golaud’s child.

...one who only hints at what is to be said. The ideal would be two associated dreams. No place, nor time. No big scene...A painting executed in grey is my ideal...No discussion or arguments between the characters whom I see at the mercy of life or destiny.

Claude Debussy to Ernest Guiraud, on what he searched for in an opera librettist and story (1889)

Composing Pelléas et Mélisande

From 1893 to 1895, the duration of the opera’s composition, Debussy remained true to the ideals he had conveyed to Ernest Guiraud. For all Golaud’s turbulent suspicion and suppurating resentment, he never does properly discuss anything or argue with Mélisande – he simply becomes brutal, but there is no proper communication at all: he is unable to communicate as he is so trapped in himself. And the portrayal of the gradually growing love between Pelléas and Mélisande is all the more touching and lifelike in that their direct expressions of passion only finally come out for a glimpse in time, just before Golaud springs out at them in the garden and kills Pelléas.

Debussy realized his ideal poetic and dramatic scenario in a musical and vocal style that was unprecedented, and it required a completely new approach from all the performers. “Forget you are singers” the composer said to the cast of Pelléas et Mélisande during rehearsals for the world premiere performance in 1902. The speech-like vocal writing was groundbreaking in opera, and yet, although the singing is close to speaking in a completely new way, Pelléas et Mélisande is written for singers. This and the interpretation of the characters themselves are issues that have aroused much debate and division among performers, scholars and audiences ever since the opera first appeared.

Forget you are singers!

Claude Debussy, during rehearsals for the world premiere performance in 1902

Performing Pelléas et Mélisande

Following now are audio files of music and discussion from the late composer and conductor Pierre Boulez, the baritone Thomas Hampson, the bass-baritone Sir Willard White, the mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade, and the baritone François Le Roux. À propos the last two artists mentioned, already on this website there is a Composer Profiles feature written for the 150th anniversary of Debussy’s birth in 2012 in which Colette Alliot-Lugaz, François Le Roux, José van Dam and Frederica Von Stade discuss the opera and some of the productions in which they have sung. All the artists’ contributions for that Debussy 150th anniversary feature, an extended version of an article that appeared in Opera Magazine, were recorded by telephone, and in the cases of François Le Roux and Frederica Von Stade large portions of the original recordings could not be included for reasons of space. For the first time, the complete conversations with both these artists are now appearing here.

In the Frederica Von Stade and François Le Roux conversations the quality of sound from the telephone is sometimes not easy on the ear, but care has been taken to make the recorded reception intelligible.

As all the artists refer to many detailed aspects of the opera’s story and personalities, the entire synopsis of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande is available to read at the foot of this feature, for contextual perspective.

In Warner Classics’ recorded performance from which all the illustrative music selections are extracted, Philippe Huttenlocher sings Golaud, Rachel Yakar is Mélisande, Eric Tappy is Pelléas, Colette Alliot-Lugaz sings Yniold, and l’Orchestre National de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo is conducted by Armin Jordan.

LISTEN TO THE AUDIO CLIPS BELOW

Track 3 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Extract from the Opening Scene of Pelléas et Mélisande with Golaud sung by Philippe Huttenlocher, and Mélisande sung by Rachel Yakar.

Track 4 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez gives an overview of Pelléas et Mélisande as theatre, music, and vocal writing.

Track 5 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Thomas Hampson gives a summary of the new musical language and style in Pelléas et Mélisande.

Track 6 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez discusses the relationship between speech and singing in Pelléas et Mélisande.

Track 7 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez discusses the relationship of the voice and orchestra à propos vocal style in Pelléas et Mélisande, plus an extract from the opening of Act III with Mélisande sung by Rachel Yakar.

Track 8 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez discusses the need to recognise that Pelléas et Mélisande is a sung opera.

Track 9 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Thomas Hampson discusses vocal requirements singing the role of Pelléas in Pelléas et Mélisande and the need to recognise that the work is a sung opera.

Track 10 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez discusses the character of Golaud in Pelléas et Mélisande, plus an extract from the end of Act III with Golaud sung by Philippe Huttenlocher and Yniold sung by Colette Alliot-Lugaz.

Track 11 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Thomas Hampson discusses the character of Golaud and the vocal writing for him in Pelléas et Mélisande.

Track 12 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez discusses the character of Mélisande in Pelléas et Mélisande, plus an extract from Act II with Mélisande sung by Rachel Yakar and Pelléas sung by Eric Tappy.

Track 13 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Pierre Boulez discusses the contrast between Golaud and the other characters in Pelléas et Mélisande, plus an extract from Act V with Golaud sung by Philippe Huttenlocher and Mélisande sung by Rachel Yakar.

Track 14 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Sir Willard White discusses Golaud’s relationship with Mélisande.

Track 15 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Frederica von Stade discusses Pelléas et Mélisande and especially the role of Mélisande (telephone recording).

Track 16 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

François Le Roux discusses Pelléas et Mélisande and especially the roles of Pelléas and Golaud (telephone recording)

(For clarification here, François Le Roux sometimes refers to Pierre Strosser (he begins by mentioning him), who was the stage director in a production of the opera in Lyon in 1986, and, in connection with the same production, when he says “José” he is referring to the bass-baritone José van Dam, who sang Golaud in that production; when he says “Menotti”, he is referring to a previous production in Paris by Gian Carlo Menotti.)

Debussy and the poets Pierre Louÿs & Edgar Allen Poe

During the period when he was composing Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy frequently visited his favourite cafés and clubs in Paris’s Montmartre district. That may seem as far away from the world of his new opera as can possibly be imagined, but in fact there is an important indirect link. It was there that he met some of the leading symbolist poets and writers of the time, and one of them was Pierre Louÿs. Three of Louÿs’ poems in a collection that he entitled Les Chansons de Bilitis were the catalyst for one of Debussy’s most deeply expressive compositions: he wrote his Trois Chansons de Bilitis in 1897 and 1898. Denis Herlin takes up the story.

Track 17 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Denis Herlin discusses Debussy’s Trois Chansons de Bilitis, plus extracts from “La Chevelure” (1897) and “Le Tombeau des Naïades” (1898), sung by Veronique Gens accompanied by Roger Vignoles.

For a long time, Debussy was deeply fascinated by the cryptic and occult world of Edgar Allen Poe, and there is certain evidence that as early as 1890 he was toying with the idea of composing an orchestral work on themes from Poe’s stories, and in particular the macabre, Gothic tale The Fall of the House of Usher. He once said that “the secret atmosphere” of Poe’s works strongly appealed to him, and he was especially taken with the stark symbolism of The Fall of the House of Usher with its silent, decaying house where Roderick Usher lives. He has some strange, indefinable disease that pathologically hypes his nervous sensitivity, and as his life crumbles, so does his house.

In due course, mainly from around 1908, Debussy began more specifically to conceive the idea of writing an opera around the story, entitling it in French La Chute de la maison Usher, but he never managed to write more than some sketches over the years. Ironically, in 1916 as he began to feel at last that he was ready to take it forward, he had by now been diagnosed with cancer and he increasingly felt himself identifying with Roderick Usher. After his death, attempts were made to complete some of the sketches and also orchestrate them, but they cannot tell us exactly how Debussy himself would have proceeded.

Instead, for its Debussy centenary edition, Warner Classics has commissioned the pianist, author and scholar Jean-Pierre Armengaud to prepare and supervise a special performing edition of the composer’s original fragments for voices and piano, which he discusses here.

Track 18 of Singers on Singing: Singing Debussy

Jean-Pierre Armengaud discusses the sketches for La Chute de la Maison Usher, plus an extract from the scene where l’Ami (the friend) reads to Roderick Usher the ancient story of “The Mad Trist.” L’Ami is spoken and sung by Jean-Christophe Lanièce, Roderick Usher is sung by Philippe Estèphe, and they are accompanied by Jean-Pierre Armengaud.

In a lonely and dispirited moment, Claude Debussy once wrote in a letter to his publisher Jacques Durand: “An artist is, by definition, a man accustomed to dream, who lives among spectres. How can anyone expect that such a man can behave in everyday life in strict observance of the traditions, laws and other barriers put there by a hypocritical and base world?” His words could almost have been a prior epitaph to the inspiration that fired his revolutionary creativity in all the genres of music that he composed.

An artist is, by definition, a man accustomed to dream, who lives among spectres. How can anyone expect that such a man can behave in everyday life in strict observance of the traditions, laws and other barriers put there by a hypocritical and base world?

Claude Debussy, in a letter to Jacques Durand

More about the Debussy Centennial:

Debussy 100

More about Warner Classics’ new 33-CD box set celebrating the Debussy Centennial

Visit siteFull Piano Score with notes

Available via the website of the William and Gayle Cook Music Library at the Indiana University School of Music

Visit siteGoogle Books: "Pelléas et Mélisande"

This first comprehensive guide to Debussy's "Pelléas et Mélisande" was written by the leading authorities on French music of the period. As a background to the opera, the authors, together with David Grayson, discuss various aspects of the play. They consider its literary roots, trace its genesis and composition, and illuminate Debussy's compositional strategies. A detailed synopsis of Debussy's musical response to the text forms a central chapter. This is followed by an examination of the symbols and musical motives employed by Debussy as well as an analysis of his themes. The book concludes with a detailed bibliography and a discography.

Visit siteGoogle Books: "The Life of Debussy"

The early music of Claude Debussy was influenced by the work of Wagner, for whom he had great admiration. However, soon Debussy's music became more experimental and individualistic, as is clear in his first mature work Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. Debussy quickly moved away from traditional techniques and produced the pictures in sound that led his work to be described as "musical Impressionism." This biography offers new insights into the life of this enigmatic composer, revealing a figure more seminal and revolutionary than previously thought.

Visit siteSynopsis of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande

ACT 1

Scene 1: A forest

Prince Golaud, grandson of King Arkel of Allemonde, has become lost while hunting in the forest. He discovers a frightened, weeping girl sitting by a spring in which a crown is visible. She reveals her name is Mélisande but nothing else about her origins and refuses to let Golaud retrieve her crown from the water. Golaud persuades her to come with him before the forest gets dark.

Scene 2: A room in the castle

Six months have passed. Geneviève, the mother of the princes Golaud and Pelléas, reads a letter to the aged and nearly blind King Arkel. It was sent by Golaud to his brother Pelléas. In it Golaud reveals that he has married Mélisande, although he knows no more about her than on the day they first met. Golaud fears that Arkel will be angry with him and tells Pelléas to find how he reacts to the news. If the old man is favorable then Pelléas should light a lamp from the tower facing the sea on the third day; if Golaud does not see the lamp shining, he will sail on and never return home. Arkel had planned to marry the widowed Golaud to Princess Ursule in order to put an end to “long wars and ancient hatreds”, but he bows to fate and accepts Golaud’s marriage to Mélisande. Pelléas enters, weeping. He has received a letter from his friend Marcellus, who is on his deathbed, and wants to travel to say goodbye to him. Arkel thinks Pelléas should wait for the return of Golaud, and also reminds Pelléas of his own father, lying sick in bed in the castle. Geneviève tells Pelléas not to forget to light the lamp for Golaud.

Scene 3: Before the castle

Geneviève and Mélisande walk in the castle grounds. Mélisande remarks how dark the surrounding gardens and forest are. Pelléas arrives. They look out to sea and notice a large ship departing and a lighthouse shining, Mélisande foretells that it will sink. Night falls. Geneviève goes off to look after Yniold, Golaud’s young son by his previous marriage. Pelléas attempts to take Melisande’s hand to help her down the steep path but she refuses saying that she is holding flowers. He tells her he might have to go away tomorrow. Mélisande asks him why.

ACT 2

Scene 1: A well in the park

It is a hot summer day. Pelléas has led Mélisande to one of his favourite spots, the “Blind Men’s Well”. People used to believe it possessed miraculous powers to cure blindness but since the old king’s eyesight started to fail, they no longer come there. Mélisande lies down on the marble rim of the well and tries to see to the bottom. Her hair loosens and falls into the water. Pelléas notices how extraordinarily long it is. He remembers that Golaud first met Mélisande beside a spring and asks if he tried to kiss her at that time but she does not answer. Mélisande plays with the ring Golaud gave her, throwing it up into the air until it slips from her fingers into the well. Pelléas tells her not to be concerned but she is not reassured. He also notes that the clock was striking twelve as the ring dropped into the well. Mélisande asks him what she should tell Golaud. He replies, “the truth.”

Scene 2: A room in the castle

Golaud is lying in bed with Mélisande at the bedside. He is wounded, having fallen from his horse while hunting. The horse suddenly bolted for no reason as the clock struck twelve. Mélisande starts to cry and says she feels ill and unhappy in the castle. She wants to go away with Golaud. He asks her the reason for her unhappiness but she refuses to say. When he asks her if the problem is Pelléas, she replies that he is not the cause but she does not think he likes her. Golaud tells her not to worry: Pelléas can behave oddly and he is still very young. Mélisande complains about the gloominess of the castle: today was the first time she saw the sky. Golaud says that she is too old to be crying for such reasons and takes her hands to comfort her. As he does so, he notices the wedding ring is missing. He becomes very agitated and then angry. Mélisande on the spur of the moment says to him she dropped it in a cave by the sea where she went to collect shells with little Yniold. Golaud orders her to go and search for it at once before the tide comes in, even though night has fallen. When Mélisande replies that she is afraid to go alone, Golaud tells her to take Pelléas along with her.

Scene 3: Before a cave

Pelléas and Mélisande make their way down to the cave in pitch darkness. Mélisande is frightened to enter, but Pelléas tells her she will need to describe the place to Golaud to prove she has been there. The moon comes out lighting the cave and reveals three beggars sleeping in the cave. Pelléas explains there is a famine in the land. He decides they should come back another day.

ACT 3

Scene 1: One of the towers of the castle

Mélisande is at the tower window, singing a song (Mes longs cheveux) as she combs her hair. Pelléas appears and asks her to lean out so he can kiss her hand as he is going away the next day. He cannot reach her hand but her long hair tumbles down from the window and he kisses and caresses it instead. Pelléas playfully ties Mélisande’s hair to a willow tree in spite of her protests that someone might see them. A flock of doves takes flight. Mélisande panics when she hears Golaud’s footsteps approaching. Golaud remonstrates with Pelléas and Mélisande for playing so late at night in the dark. Laughing nervously, he dismisses them as nothing but a pair of children and leads Pelléas away.

Scene 2: The vaults of the castle

Golaud leads Pelléas down to the castle vaults, which contain the dungeons. He asks Pelléas if he can smell the stench of death in the stagnant pool and he tells him to lean over and look into the chasm and be careful that he does not slip and fall in, holding his arm so that he does not fall. Pelléas is frightened by the stifling atmosphere, and Golaud leads him out.

Scene 3: A terrace at the entrance of the vaults

Pelléas is relieved to breathe fresh air again. It is noon. He sees Geneviève and Mélisande at a window in the tower. Golaud tells Pelléas that there must be no repeat of the “childish game” between him and Mélisande last night. Mélisande is pregnant and the least shock might disturb her health. It is not the first time he has noticed there might be something between Pelléas and Mélisande but Pelléas should avoid her as much as possible without making this look too obvious.

Scene 4: Before the castle

Golaud sits with his little son, Yniold, in the darkness of night and questions him about Pelléas and Mélisande. The boy reveals little that Golaud wants to know since he is too innocent to understand what his father is trying to find out from him. He says that Pelléas and Mélisande often quarrel about the door and that they have told Yniold he will one day be as big as his father. As Golaud presses Yniold, the child remembers that he did once see Pelléas and Mélisande kiss “when it was raining”. Golaud lifts his son on his shoulders to spy on Pelléas and Mélisande through the window but Yniold says that they are doing nothing other than looking at the light. He says he will scream if Golaud doesn’t take him down again. Golaud leads him away.

ACT 4

Scene 1: A room in the castle

Pelléas tells Mélisande that his father is getting better and has asked him to leave with him on his travels. He arranges a last meeting with Mélisande by the Blind Men’s Well in the park.

Scene 2: The same

Arkel tells Mélisande how he felt sorry for her when she first came to the castle “with the strange, bewildered look of someone constantly awaiting a calamity.” But now that is going to change and Mélisande will “open the door to a new era that I foresee.” He asks her to kiss him. Golaud bursts in with blood on his forehead — he says it was caused by a thorn hedge. When Mélisande tries to wipe the blood away, he angrily orders her not to touch him and demands his sword. He says that another peasant has died of starvation. Golaud notices Mélisande is trembling and tells her he is not going to kill her with the sword. He mocks the “great innocence” Arkel says he sees in Mélisande’s eyes. He commands her to close them or “I will shut them for a long time.” He tells Mélisande that she disgusts him and he drags her around the room by her hair. When he leaves, Arkel asks Mélisande if he is drunk. “No” she says, “but he does not love me any more. I am not happy”. Arkel comments “If I were God, I would have pity on the hearts of men.”

Scene 3: A well in the park

Yniold tries to lift a boulder to free his golden ball, which is trapped between it and some rocks. As darkness falls, he hears a flock of sheep suddenly stop bleating. A shepherd explains that they have turned onto a path that doesn’t lead back to the sheepfold, but he does not answer when Yniold asks where they will sleep. Yniold goes off to find someone to talk to.

Scene 4: The same

Pelléas arrives alone at the well. He is worried that he has become deeply involved with Mélisande and fears the consequences. He knows he must leave, but first he wants to see Mélisande one last time and tell her things he has kept to himself. Mélisande arrives. She was able to slip out without Golaud noticing. Pelléas confirms that now he is going away for ever and when Mélisande asks him why he keeps saying that, he replies “Must I tell you what you already know? Do you not know that it is because….” and after he suddenly kisses her he tells her “I love you?” To his amazement, Mélisande replies “I love you too”, and she says to him that she has loved him since she first saw him. Pelléas hears the servants shutting the castle gates for the night. Now they are locked out, but Mélisande says that it is for the better. Pelléas is resigned to fate too. Mélisande hears something moving in the shadows. It is Golaud, who has been watching silently from behind a tree in the bushes. As Pelléas and Mélisande embrace passionately, Golaud bursts out on them and strikes down Pelléas with his sword, killing him. Mélisande is also wounded but she flees into the woods crying out that he has no more courage.

ACT 5

A bedroom in the castle

Mélisande sleeps in a sick bed after giving birth to her child. The doctor assures Golaud that despite her wound, her condition is not serious. Overcome with guilt, Golaud claims he has killed for no reason. Pelléas and Mélisande merely kissed “like a brother and sister.” Mélisande wakes and asks for a window to be opened so she can see the sunset. Golaud asks the doctor and Arkel to leave the room so he can speak with Mélisande alone. He blames himself for everything and begs Melisande’s forgiveness. He presses her to tell him if she had a forbidden love for Pelléas. With just a few faint words she maintains her innocence but Golaud increasingly desperately pleads with her to tell him everything. Arkel and the doctor return. Arkel tells Golaud to stop before he kills Mélisande, but he replies “I have already killed her.” Arkel hands Mélisande her newborn baby girl, but she is too weak to lift the child in her arms and remarks that the baby does not cry and that she will live a sad existence. The room fills with serving women, although no one can tell who has summoned them. Mélisande quietly dies. At the moment of death, the serving women fall to their knees. Arkel comforts the sobbing Golaud.