Program Notes by Thomas Hampson

and Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold (1998)

Thomas Hampson, baritone / Craig Rutenberg, piano

Sunday, May 31, 1998

Unspecified Location

This program also includes song texts in English.

One of the most provocative dichotomies of the Romantic age was its yearning for freedom from stasis—for a relentless forward-thrusting dynamic—juxtaposed with its longing to return to a gentler time. This nostalgia was expressed vividly in the pan-European and American Folk Movements of the last two and a half centuries. ln the late 1800s, reminiscences of a vanishing rural existence, together with the rising Romantic rebellion against the restraints of artistic formula and convention, prompted creative thinkers to plumb what Goethe called the Volkslied as a fount of fresh expressive possibilities and a source of unsullied truth. Wordsworth and Coleridge, echoing Robert Burns’ democratic humanism (“A man’s a man for all of that”) sounded a battle cry in their 1797 publication of Lyrical Ballads, insisting poetry must be written in the language of the common man. Throughout Europe, poets, composers, and visual artists immersed themselves in the imagistic language of a folk tradition that dated back to medieval times; systematically, they set about to research those traditions while artistically, they absorbed them into their creative psyches to be reborn in new, modern works.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

The program begins with a group of musically and poetically intertwined songs inspired by the Folk Movement. When Stephen Collins Foster determined to become America’s first professional songwriter, he turned for inspiration to, among others, the Scots-Irish melodies of his childhood. Three seminal collections of the late 18th and early 19th centuries enjoyed overwhelming popularity not only in Europe, but in America as well: James Johnson’s Scots-Irish Musical Museum, to which Robert Burns was a primary contributor; George Thomson’s National Airs; and Thomas Moore‘s Irish Melodies. One of Foster’s earliest musical memories was of his older sister Charlotte playing and singing Moore’s haunting lyric, “Oft in the Stilly Night,” and he surely had Burns’ “My Love ls Like a Red, Red Rose” in mind when he composed his own “Ah! May the Red Rose Live Alway!” Not only did Foster seek to emulate Burns’ and Moore’s tenderness of lyrical expression and passion for the common man, but he also sought to absorb their sentiment-rich vocabulary, their unerring instinct for capturing rhythms of their native dialects, and their belief that poetry consisted of words meant to be sung, not read! “There is blood on every page that Burns writes,” Walt Whitman once declared. The same could have been said of Moore, whose unabashed lrish patriotism, as voiced in “The Minstrel Boy,” turned the drawing rooms of which he was an idol into salons of subtle subversiveness.

In George Butterworth’s A Shropshire Lad, the deceptively simple folk idiom lends an edge of bitter irony to the cycle, drawn from A.E. Housman‘s collection of poems of the same title. When the twenty-one-year-old Butterworth turned to Housman’s poems in 1906, he was responding, as had five other contemporary composers, to the Edwardian poet’s mask of self-imposed restraint which modulated into a seething emotional ‘life beneath—to Housman’s juxtaposition of regret and defiance, repression and longing, faith and despair—a blend of nostalgic metaphor and mood which seemed an highly appropriate antidote to the uncertain new century.

Housman, who had spent his life in the lonely ivory tower of a Classics scholar, who had translated the complete works of the Stoic Manlius, and who had taught Latin to generations of youths at London and Cambridge Universities, had written only three slim volumes of verse in his seventy-seven years, all born from the anguish of an unrequited attachment for his university comrade Moses Jackson, by his separation from Jackson who joined the military Raj, and ultimately by Jackson’s death in 1923. Of these, the sixty-three poems he self-published in 1896 as A Shropshire Lad speak most fervently of what the poet himself called “a land of lost content”—a partly imaginary rural landscape where idyllic chimera link arms with the harsh realities of war, lost innocence, and lost love in a danse macabre, that for all its bleakness still sparkles with an unrepentant Romantic faith.

The first three songs, “Loveliest of trees,” “When I was one and twenty,” and “Look not in my eyes,” are simple, lyrical, and lilting in their vocal lines, as the poet and composer reflect on the transience of life, the brevity of beauty, and the folly of falling in love. The turning point arrives, however, in the jerking chords of “Think no more lads,” which paves the way for the impending doom of the war-bound lads at Ludlow fair and for “Is my team ploughing?,” the chilling dialogue between two comrades—one in his grave, the other his replacement in the arms of his beloved. The listener’s knowledge that within ten years of composing this cycle Butterworth would be dead—killed at the Battle of Somme on August 5, 1916, at the age of thirty-one—serves only to intensify the crushing ironies and poignancy of the work.

That the American composer Samuel Barber was also drawn to Housman’s poetry (“With rue my heart is laden”) is no surprise, given the spiritual and temperamental kinship poet and composer seemed to share. Both were patrician spirits who wore their articulate urbanity as a mask, and both were artists who struggled with the contradictions and correspondences between Classicism and Romanticism. The conflicts of intellect and emotion, of restraint and abandon, of classical and modernistic reserve versus Romantic melody, of the simplicity of the folk idiom transformed into the sophistication of the art song all shaped the dynamics of Barber’s work.

Nephew of the famed contralto Louise Homer and her song-writer husband, Sidney Homer, music was Samuel Barber’s birthright. He studied piano at six, began composing at seven, served as church organist while still in his teens, and developed his attractive baritone voice to the point where he seriously considered becoming a professional singer. Trained at the Curtis lnstitute (with its faculty steeped in the 19th century European tradition) and in Rome, where he formed his life-long friendship with Giancarlo Menotti, Barber composed a wide range of stage, orchestral, piano, choral, and vocal works. Widely read in and deeply committed to poetry, he turned frequently to the English Romantics and mystics, the Georgian School, the lrish bards, and the French Symbolists for inspiration, cultivating their interest in nature, their economy of language and line, their ironic bent, and their distinctly modern pessimism.

The six songs of this evening’s program reflect Barber’s fascination with the Anglo-Celtic tradition. The group begins with the lilting folk-styled melody for James Stephens‘ “The Daisies” and ends with the whimsical detachment of “Solitary Hotel” from Joyce‘s Ulysses, meandering in between through the tight-lipped pathos of “With Rue My Heart is Laden,” tie demonic despair of W. H. Davies’ “Night Wanderers,” and the grim melancholy of Joyce’s “Rain has fallen” and his translation from Gottfried Keller of “Now I have fed and eaten up the rose.” Each is a miniature drama in which contemporary skepticism subtly gives way to persistent Romanticism, while never losing hold of the emotional and technical balance that characterize the Classical legacy.

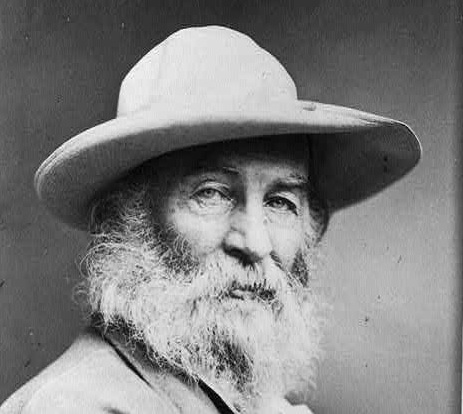

The catholicity of Barber’s taste in poetry provided an effective transition to the catholicity of musical styles used to set the texts of America’s great 19th century poet, Walt Whitman, whose appeal as a poetic source for song composers was truly international. There are over four hundred known solo song settings of Whitman’s poems by American, British, French, Scandinavian, German, ltalian, and Russian composers. The English-language group which concludes today’s program, samples some of that diversity of idiom, including four native-born American composers and three naturalized American citizens, who embraced Whitman as the voice of their new adoptive land.

Whitman, who once wrote, “I am large, I contain multitudes,” would surely have delighted in the contrasts as well as the confluence of the seven songs that constitute the second half of tonight’s program. These begin with the Afro-centric rhythmic origins of Burleigh‘s “Ethiopia Saluting the Colors” segueing to the nascent modernism that never quite loses sight of the richness of melody in Rorem‘s “As Adam Early in the Morning,” and on to the tripartite mini-cantata of Neidlinger‘s “Memories of Lincoln,” with its intimations of the ballad, choral, and ecclesiastical traditions in which the composer was nurtured. This modulates into the shimmering impressionism of Cairo-born Naginski‘s “Look Down Fair Moon,” followed by the spare simplicity of Hindemith‘s “Sing on There in the Swamp,” taken from his Requiem that was composed to celebrate his taking of American citizenship, before moving on to the pulsating “Dirge for Two Veterans” in which Weill fuses the percussive emotion of Whitman’s Drum Taps with the plangent melodies of his Berlin homeland, and finally to the long-lined declamation ensconced in subtle pianistic rhetoric of Bernstein’s “To What You Said.”

With Whitman, as with all the poets and composers of today’s program, one hears a contrasting dynamic of propulsive narrative and lyric stasis, between the storyteller’s drama of the ballad and the psychological drama of the Lied, between the nostalgia for a gentler, quieter world—now gone—and the need for a vigorous thrust forward into Whitman’s “unknown region where all awaits undream’d of.” The poet who, at the close of “Song of Myself,” writes, “Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,/ Missing me one place search another,/ I stop somewhere waiting for you,” extends the invitation to his reader to voyage, to become a wanderer who abandons stasis and embraces flux, discovering as Romantics from the 19th century to the present have, that mankind’s fate appears to hinge on accepting the peregrinations of poetry and life.

File Download

Program Notes by Thomas Hampson

and Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold